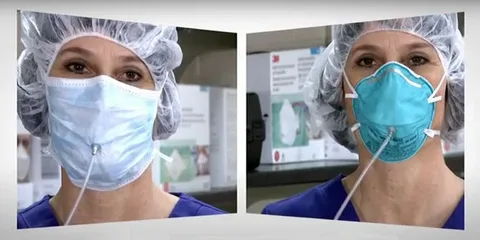

The open letter emphasised that respirators, such as N95, FFP2, and FFP3 models, offer significantly better filtration and fit, reducing the amount of infectious material inhaled. It argued that continuing to present basic masks as adequate protection, without clearly distinguishing their limitations, creates a false sense of security, particularly in high-risk environments like hospitals, public transport, and crowded indoor spaces.

While headlines quickly focused on the phrase “face masks inadequate”, the substance of the letter, and the broader implications of its claims, received far less careful examination. Yet it is this document, not speculation or sudden institutional reversal, that explains why the WHO’s guidance is being questioned and reconsidered.

The letter did not accuse the WHO of negligence, nor did it dismiss the value of masks entirely. Instead, it made a specific, evidence-based argument, that public health guidance has lagged behind what is now well established about airborne transmission. The authors contended that guidance still heavily reflects early assumptions about droplet spread, despite mounting scientific evidence that inhalation of airborne particles is a dominant transmission route for many respiratory illnesses.

The renewed global conversation about face masks began with an open letter. Addressed directly to the World Health Organisation, the letter was signed by a group of scientists, engineers, and public health experts who argued that commonly used face masks are insufficient for protection against airborne diseases and should, in many settings, be replaced with respirators.

This is the context in which the WHO’s advice must be understood. It did not emerge suddenly or arbitrarily. It was prompted by sustained scientific pressure and a growing consensus that guidance needs to reflect how diseases actually spread, not how it was once assumed they did.

This distinction matters. Droplet-based protection focuses on blocking larger particles that fall quickly to the ground. Airborne protection focuses on filtering tiny particles that can remain suspended in the air for extended periods, especially indoors. According to the signatories, many standard masks, particularly cloth and surgical masks, were never designed to provide reliable protection against these particles.

The letter also addressed a long-standing gap between occupational safety standards and public health messaging. In industrial and laboratory settings, respirators have long been the accepted standard for protection against airborne hazards. The authors questioned why a lower standard has been normalised for healthcare workers and the general public during outbreaks of airborne disease. This inconsistency, they argued, would be unacceptable in other safety-critical fields.

Importantly, the letter did not call for the abandonment of masks altogether. It acknowledged that masks can reduce emission of respiratory particles and offer some level of protection. However, it stressed that partial protection should not be confused with adequate protection, particularly when better options exist and the risks are high.

The WHO’s response, and subsequent advisory language, reflects a careful balancing act. On one hand, it recognises the scientific validity of the concerns raised. On the other, it must consider global feasibility. Respirators require proper fitting, training, and consistent supply. They are more expensive and less comfortable for prolonged use. Public health guidance cannot ignore these realities.

This tension between scientific ideal and practical implementation has shaped much of the pandemic-era guidance. Early recommendations prioritised measures that could be deployed quickly and broadly. Over time, as evidence accumulated and supply chains stabilised, the justification for sticking rigidly to those early compromises weakened.

What makes the open letter significant is not just its content, but its framing. It shifts the conversation from whether masks work at all to how much protection is enough, and in what circumstances. This reframing moves the discussion away from polarised debates and towards risk-based decision-making.

The letter also situates respiratory protection within a wider strategy that includes ventilation, air filtration, and indoor air standards. The authors argued that focusing narrowly on masks, while ignoring air quality, has limited the effectiveness of public health responses. Respirators, in this view, are part of a layered approach rather than a standalone fix.

From an evergreen perspective, this debate extends beyond any single disease or emergency. Airborne transmission is not unique to pandemics. Seasonal illnesses, workplace exposures, and future outbreaks all raise similar questions about how societies protect people in shared indoor spaces. The letter to the WHO can be seen as part of a broader push to modernise public health thinking around air, much as water and food safety were modernised in previous decades.

The public reaction to the WHO’s updated stance has often overlooked this continuity. Some have interpreted it as an admission that earlier guidance was wrong. Others see it as an overreaction. In reality, it represents an evolution driven by better data, clearer understanding, and sustained expert engagement.

The open letter matters because it demonstrates how scientific discourse influences policy, even within large institutions. It shows that guidance is not fixed by authority alone, but shaped through challenge, evidence, and debate. This process is often invisible to the public until it produces a headline.

For readers trying to make sense of the issue, the key lesson is not that masks suddenly failed, but that protection standards are being recalibrated. The question is no longer whether face coverings have a role, but whether they are sufficient in environments where airborne risk is high and prolonged.

By bringing this issue into the open, the letter has forced a more honest conversation about limitations, trade-offs, and priorities. It has highlighted the need for clearer communication that distinguishes between minimal, moderate, and optimal protection, rather than presenting a single measure as universally adequate.

In the long term, the significance of this moment may lie less in mask policy and more in how public health adapts to complexity. The move towards respirator advice signals a shift away from simplified messaging towards more nuanced, context-aware guidance. That shift, while uncomfortable, is necessary if trust is to be maintained and protection genuinely improved.

The open letter did not demand certainty. It demanded alignment between evidence and advice. In doing so, it has reshaped the conversation, not by being loud, but by being precise.